"I try to look for something that says something mysterious or absurd or extremely simple or extremely complicated--" explained Lichtenstein, " something that when it's a part of a painting will strike you as funny." One writer explained,

"I try to look for something that says something mysterious or absurd or extremely simple or extremely complicated--" explained Lichtenstein, " something that when it's a part of a painting will strike you as funny." One writer explained,

Lichtenstein intends to raise images from popular culture to the level of high art by transforming it in his work. He takes devalued forms of viusal communication, redeems them, and possesses them through recreating them in his paintings. Because he has considered and minutely adjusted every line, form and color area, his art breathes finesse and refinement.Lichtenstein believed that he paid more attention to form than the commercial artists whose work he appropriated. "What I do is form, whereas the comic strip is not formed in the sense that I'm using the word. The comics have shapes, but there has been no effort to make them intesnely unified. The purpose is dfifferent -- one intends to depct and I intend to unify. And my work is actually different from the comic strips in that every mark is in a different place, however slight the differences seem to some. The difference is often not great, but it is crucial."

The subject of his art is the artificiality of communication. "Because you're starting with somebody else's art, it says something about communication. You're not looking at a nature garden or something. You're taking known symbols and styles of things and recreating them." - Roy Lichtenstein

When viewers first saw his work, many were so outraged by the source of subject matter that they could not begin to appreciate the formal qualities of the work. "

His critics were confused as to what his attitude toward the comics was. "I think of it as an ironic look at and use of what is usually called vulgar art," he explained. "It's using those symbols to make something else. It's really the art we have around us; we're not living in the word of Impressionist painting. For me, it has a 'you're a bad boy copying comics' thing because our art teacher told us not to copy, and if you did copy, it certainly wouldn't be commercial art."I always think that its' the formal part that gets neglected and that usually people talk about what the subject means, and when they do that, it sounds fairly obvious. I think it's the formal part that nobody understands. It is the kinesthetic and visual sense of position and wholeness that puts the thing in the realm of art. For most people, the formal part is not what they see. One may be influeced by the sense of formand think it's really all right without understnading why. But the understanding of form is limited because I think people don't tend to see it unless they are artists. -Lichtenstein

What he saw in mechanical production of artwork was a lack of nuance. There is a red and there's 50% red. They don't care what kind of pink is used. He aimed to take the least elegant thing he could find and tried to make something elegant out of it.

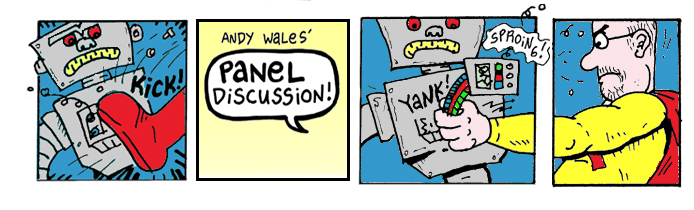

Okay Hot Shot is a painting that is based on comics, but this particular images exists nowhere in any one comic. He put four different comics panels together. The reference to 'pouring" is an art world in-joke. It refers to Morris Louis' brand of modern painting, using poured paint. Lichtenstein delighted in the double take. Possibly this was his tongue in cheek reaction to critics who claimed that pouring (as opposed to his comics paintings) would have been "real art".

Okay Hot Shot is a painting that is based on comics, but this particular images exists nowhere in any one comic. He put four different comics panels together. The reference to 'pouring" is an art world in-joke. It refers to Morris Louis' brand of modern painting, using poured paint. Lichtenstein delighted in the double take. Possibly this was his tongue in cheek reaction to critics who claimed that pouring (as opposed to his comics paintings) would have been "real art".

Conversation (1962) is one of Lichtenstein's rare drawings that were not done as a study for a painting. He was fond of visual puns. Though it is called conversation, there is no speech balloon. It was about this time that he stopped using them for a while. He emphasizes the harsh angular lines in the man's face and emphasizes the soft curves in the woman's. The man's expression is obscured from view, but seems calm, while the woman appears to be in shock. This is more than a man copying comic books. He is presenting our stereotypes and forcing us to think about them.

He emphasizees the dots between the faces in such a way that the shape refuses to recede into the background as it should. It becomes a focal point. The picture plane is all-important, as he felt that was what made paintings modern. We can tell by his sketches that he labored over each line. He would create several different versions and studies preparing for the major canvasses. The contour line itself was drawn in outlines and then filled in, giving it a distinctly object-like character. He insisted that the line both described the object and existed in its own right. "I think Matisse is like that; the mark is just the mark and it may be part of the same arm, but you can see how he does think about it as separate (Rose, 1987)."

Art History

When he paid tribute to an art history icon from the past, he didn't refer directly to a Picasso, for instance, but looked at a poor reproduction of one. As he sought to find ideas to rework in his own image, he investigated the age-old question of what constitutes art. While doing so in his homages to other artists, he was conscious of his own place in art history. He saw himself as part of a continuous line of descent beginning with Medieval art. Art began as only religious but began to include common people, beggars, still lifes, and landscapes. Cubists then began to use bits of newspaper and wallpaper. He saw this "vulgarizing" as part of recent art history and as crucial -- of things becoming more vernacular.

No comments:

Post a Comment